Pricing Guides & Dictionary of Makers Marks for Antiques & Collectibles

A few examples of appraisal values for

YOUNG AMERICAN

Search our price guide for your own treasures

-

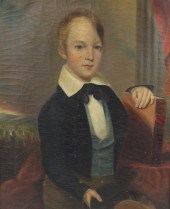

AMERICAN (19TH CENTURY) YOUNG BOY

AMERICAN (19TH CENTURY) YOUNG BOY Oil on canvas: 26 1/2 x 21 1/4 in. Framed

AMERICAN (19TH CENTURY) YOUNG BOY

AMERICAN (19TH CENTURY) YOUNG BOY Oil on canvas: 26 1/2 x 21 1/4 in. Framed -

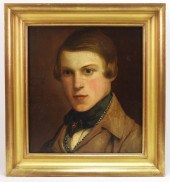

19C AMERICAN SCHOOL HANDSOME

19C AMERICAN SCHOOL HANDSOME YOUNG MAN PAINTING United States19th CenturyDepicts a young man with pale brown hair, blue eyes, and flushed cheeks dressed in a tan suit jacket with red jeweled tie clip.

19C AMERICAN SCHOOL HANDSOME

19C AMERICAN SCHOOL HANDSOME YOUNG MAN PAINTING United States19th CenturyDepicts a young man with pale brown hair, blue eyes, and flushed cheeks dressed in a tan suit jacket with red jeweled tie clip. -

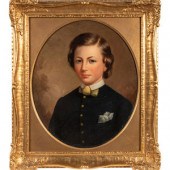

AMERICAN PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG BOY.

AMERICAN PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG BOY. Third quarter 19th century, oil on canvas. Serious looking youth in a high button jacket and plaid tie. Patches, over paint and has been re-varnished. Oval canvas 24"h. 20"w. Oval frame 32.5"h. 28.5"w.

AMERICAN PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG BOY.

AMERICAN PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG BOY. Third quarter 19th century, oil on canvas. Serious looking youth in a high button jacket and plaid tie. Patches, over paint and has been re-varnished. Oval canvas 24"h. 20"w. Oval frame 32.5"h. 28.5"w. -

AMERICAN FOLK PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG

AMERICAN FOLK PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG CHILD. Second quarter-19th century. Oil on canvas, unsigned. Well done image of a blond boy dressed in white with a blue sash. Crazing and a few scuffed areas with inpainting. 24"h. 20"w., gilt frame, 26.5"h. 22.5"w.

AMERICAN FOLK PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG

AMERICAN FOLK PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG CHILD. Second quarter-19th century. Oil on canvas, unsigned. Well done image of a blond boy dressed in white with a blue sash. Crazing and a few scuffed areas with inpainting. 24"h. 20"w., gilt frame, 26.5"h. 22.5"w. -

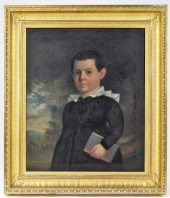

19C. AMERICAN O/C PORTRAIT PAINTING

19C. AMERICAN O/C PORTRAIT PAINTING OF A YOUNG BOY United States,19th CenturyDepicting a finely dressed young boy holding a spelling book standing in front of trees with a blue sky landscape in the background.

19C. AMERICAN O/C PORTRAIT PAINTING

19C. AMERICAN O/C PORTRAIT PAINTING OF A YOUNG BOY United States,19th CenturyDepicting a finely dressed young boy holding a spelling book standing in front of trees with a blue sky landscape in the background. -

American School (21st Century)

American School (21st Century) "Portrait of Young Child in Blue", oil on canvas, 16" x 12". Presented in a carved giltwood frame.

American School (21st Century)

American School (21st Century) "Portrait of Young Child in Blue", oil on canvas, 16" x 12". Presented in a carved giltwood frame. -

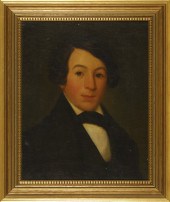

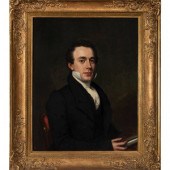

AMERICAN SCHOOL19th CenturyBust

AMERICAN SCHOOL19th CenturyBust portrait of a young man with brown eyes brown hair and brown jacket with white stock.Oil on canvas relined 20 x 16''. Framed.''

AMERICAN SCHOOL19th CenturyBust

AMERICAN SCHOOL19th CenturyBust portrait of a young man with brown eyes brown hair and brown jacket with white stock.Oil on canvas relined 20 x 16''. Framed.'' -

Engraving ''Young America''

Engraving ''Young America'' Crushingrebellion 1864 image area 12-1/2'' x 9''

Engraving ''Young America''

Engraving ''Young America'' Crushingrebellion 1864 image area 12-1/2'' x 9'' -

American School, 19th Century

American School, 19th Century Portrait of a Young Man with Book oil on panel 32 x 24 3/4 inches (sight).

American School, 19th Century

American School, 19th Century Portrait of a Young Man with Book oil on panel 32 x 24 3/4 inches (sight). -

American School 19th Century

American School 19th Century Portrait of a Young Man Estimate:$800-$1,200

American School 19th Century

American School 19th Century Portrait of a Young Man Estimate:$800-$1,200 -

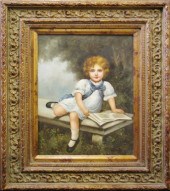

AMERICAN PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG GIRL

AMERICAN PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG GIRL PAINTING United States,19th CenturyNaturalistic depiction of a curly headed child dressed in white gazing towards a lush landscape.

AMERICAN PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG GIRL

AMERICAN PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG GIRL PAINTING United States,19th CenturyNaturalistic depiction of a curly headed child dressed in white gazing towards a lush landscape. -

19C YOUNG BABY TODDLER BOY FOLK ART

19C YOUNG BABY TODDLER BOY FOLK ART PAINTING United States19th CenturyDepicts a young child with brunette hair and large blue eyes dressed in a deep blue outfit.

19C YOUNG BABY TODDLER BOY FOLK ART

19C YOUNG BABY TODDLER BOY FOLK ART PAINTING United States19th CenturyDepicts a young child with brunette hair and large blue eyes dressed in a deep blue outfit. -

American oil on canvas portrait

American oil on canvas portrait of a young man mid 19th c. 30" x 25". ?

American oil on canvas portrait

American oil on canvas portrait of a young man mid 19th c. 30" x 25". ? -

AMERICAN SCHOOL (19TH/20TH CENTURY)

AMERICAN SCHOOL (19TH/20TH CENTURY) PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG GIRL Oil on canvas: 21 x 14 in. Framed

AMERICAN SCHOOL (19TH/20TH CENTURY)

AMERICAN SCHOOL (19TH/20TH CENTURY) PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG GIRL Oil on canvas: 21 x 14 in. Framed -

AMERICAN O/C PORTRAIT PAINTING OF A

AMERICAN O/C PORTRAIT PAINTING OF A YOUNG GIRL United States,20th CenturyNaturalist depiction of a young blonde haired, blue eyed child biting into an apple with a basket hanging off her arm.

AMERICAN O/C PORTRAIT PAINTING OF A

AMERICAN O/C PORTRAIT PAINTING OF A YOUNG GIRL United States,20th CenturyNaturalist depiction of a young blonde haired, blue eyed child biting into an apple with a basket hanging off her arm. -

AMERICAN SCHOOLLate 19th

AMERICAN SCHOOLLate 19th CenturyPortrait of Arthur Young as a baby wearing a white gown. Unsigned.Provenance: Private Collection Cape Cod Massachusetts.Oil on canvas 16 x 13''. Framed.''

AMERICAN SCHOOLLate 19th

AMERICAN SCHOOLLate 19th CenturyPortrait of Arthur Young as a baby wearing a white gown. Unsigned.Provenance: Private Collection Cape Cod Massachusetts.Oil on canvas 16 x 13''. Framed.'' -

AMERICAN SCHOOL, PORTRAIT OF A

AMERICAN SCHOOL, PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG MANAmerican School19th centuryPortrait of a young manpastel24 x 18in (61 x 45.5cm)

AMERICAN SCHOOL, PORTRAIT OF A

AMERICAN SCHOOL, PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG MANAmerican School19th centuryPortrait of a young manpastel24 x 18in (61 x 45.5cm) -

AMERICAN SCHOOL19th CenturyPortrait

AMERICAN SCHOOL19th CenturyPortrait of a young woman with a lace collar. Unsigned.Oil on canvas 13 x 10''. Framed.''

AMERICAN SCHOOL19th CenturyPortrait

AMERICAN SCHOOL19th CenturyPortrait of a young woman with a lace collar. Unsigned.Oil on canvas 13 x 10''. Framed.'' -

Young Girl in a White Dress

Young Girl in a White Dress American 19th century.?Oil on canvas in a gilt and gesso decorative frame; 23.25 x 17 in. (sight). Condition: Craquelure throughout. Light inpainting along right perimeter.

Young Girl in a White Dress

Young Girl in a White Dress American 19th century.?Oil on canvas in a gilt and gesso decorative frame; 23.25 x 17 in. (sight). Condition: Craquelure throughout. Light inpainting along right perimeter. -

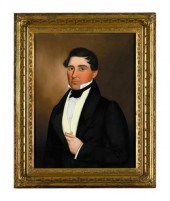

American School, 19th Century

American School, 19th Century Portrait of a Young Man oil on canvas 25 7/8 x 21 7/8 inches.

American School, 19th Century

American School, 19th Century Portrait of a Young Man oil on canvas 25 7/8 x 21 7/8 inches. -

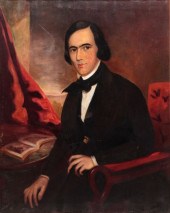

PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG MAN. American

PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG MAN. American school, mid 19th century. Oil on canvas, unsigned. Man with a walking stick, seated at a table with a book showing printed plates. Some surface wear and indentations, minor inpainting. 36.75"h. 29.5"w., modern frame, 42"h. 34.75"w.

PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG MAN. American

PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG MAN. American school, mid 19th century. Oil on canvas, unsigned. Man with a walking stick, seated at a table with a book showing printed plates. Some surface wear and indentations, minor inpainting. 36.75"h. 29.5"w., modern frame, 42"h. 34.75"w. -

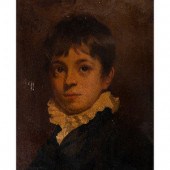

AMERICAN SCHOOLFirst Half of the

AMERICAN SCHOOLFirst Half of the 19th CenturyHalf-length portrait of a young man wearing a black coat and white stock. Unsigned.Oil on canvas 10 x 8''. Framed.''

AMERICAN SCHOOLFirst Half of the

AMERICAN SCHOOLFirst Half of the 19th CenturyHalf-length portrait of a young man wearing a black coat and white stock. Unsigned.Oil on canvas 10 x 8''. Framed.'' -

American School, 19th century

American School, 19th century portrait of a young man Unsigned, pastel on paper, framed. 19 1/2 x 15 in. PROVENANCE: The collection of James and Candace McIlhenny, Alexandria, Virginia. ,000-1,500 Good condition

American School, 19th century

American School, 19th century portrait of a young man Unsigned, pastel on paper, framed. 19 1/2 x 15 in. PROVENANCE: The collection of James and Candace McIlhenny, Alexandria, Virginia. ,000-1,500 Good condition -

AMERICAN PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG GIRL

AMERICAN PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG GIRL PAINTING United States,19th CenturyDepicts a young girl kneeling in a yellow dress.

AMERICAN PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG GIRL

AMERICAN PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG GIRL PAINTING United States,19th CenturyDepicts a young girl kneeling in a yellow dress. -

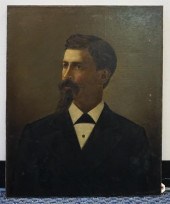

American school (19th century)

American school (19th century) PORTRAIT OF YOUNG MAN oil on canvas framed unsigned H20'' W17'' Provenance: Estate of Marjorie V. Gibbs Yemassee South Carolina. Back   Inquiry    Previous Item  Next Item © Charlton Hall Auctions. Images descriptions and condition reports used on this site are original copyright material and are not to be reproduced without permission. For further information telephone 803.779.5678   © 2012 CHARLTON HALL GALLERIES INC.

American school (19th century)

American school (19th century) PORTRAIT OF YOUNG MAN oil on canvas framed unsigned H20'' W17'' Provenance: Estate of Marjorie V. Gibbs Yemassee South Carolina. Back   Inquiry    Previous Item  Next Item © Charlton Hall Auctions. Images descriptions and condition reports used on this site are original copyright material and are not to be reproduced without permission. For further information telephone 803.779.5678   © 2012 CHARLTON HALL GALLERIES INC. -

American School, 19th Century

American School, 19th Century Portrait of a Young Boy in the manner of Thomas Sully oil on board Sight 15 3/4 x 13 inches. Property of a Southern Collector, Russellville, Kentucky

American School, 19th Century

American School, 19th Century Portrait of a Young Boy in the manner of Thomas Sully oil on board Sight 15 3/4 x 13 inches. Property of a Southern Collector, Russellville, Kentucky -

American School (19th Century).

American School (19th Century). Portrait of a young boy. Oil on canvas, approx. 21" x 16-3/4", framed in a gilt frame overall approx. 24" x 20".

American School (19th Century).

American School (19th Century). Portrait of a young boy. Oil on canvas, approx. 21" x 16-3/4", framed in a gilt frame overall approx. 24" x 20". -

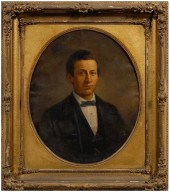

19th century American portrait,

19th century American portrait, young man, possibly an Ohioan, unsigned, oil on canvas, Closson Art Gallery label verso, 29-7/8 x 24-1/2 in.; original 19th century gilt wood and composition cove molding frame, pepple decorated spandrel, fruit and floral corner and center decoration. Original stretcher and tacking edge, crackle, 1 in. tear, grime, canvas loose, areas of retouch with about 5 percent of surface affected; frame with losses, repairs, some resurfacing. Collection of Ella Watson Haggard, Lexington, Kentucky.

19th century American portrait,

19th century American portrait, young man, possibly an Ohioan, unsigned, oil on canvas, Closson Art Gallery label verso, 29-7/8 x 24-1/2 in.; original 19th century gilt wood and composition cove molding frame, pepple decorated spandrel, fruit and floral corner and center decoration. Original stretcher and tacking edge, crackle, 1 in. tear, grime, canvas loose, areas of retouch with about 5 percent of surface affected; frame with losses, repairs, some resurfacing. Collection of Ella Watson Haggard, Lexington, Kentucky. -

American School (Mid-20th Century).

American School (Mid-20th Century). Portrait of a young man. Oil on canvas, no signature found, approx. 20-1/4" x 16", framed in a gilt frame overall approx. 26" x 22-1/4".

American School (Mid-20th Century).

American School (Mid-20th Century). Portrait of a young man. Oil on canvas, no signature found, approx. 20-1/4" x 16", framed in a gilt frame overall approx. 26" x 22-1/4". -

AMERICAN SCHOOL: PORTRAIT OF A

AMERICAN SCHOOL: PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG MAN Oil on canvas mounted on masonite unsigned. 21 x 17 1/4 in. (sight) 31 1/2 x 28 in. (frame).

AMERICAN SCHOOL: PORTRAIT OF A

AMERICAN SCHOOL: PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG MAN Oil on canvas mounted on masonite unsigned. 21 x 17 1/4 in. (sight) 31 1/2 x 28 in. (frame). -

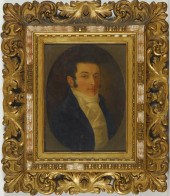

AMERICAN SCHOOL (CIRCA 1830),

AMERICAN SCHOOL (CIRCA 1830), PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG MAN WITH BOOK Oil on panel, unsigned, presented in a period hardwood frame with ebonized and gilt surface.

AMERICAN SCHOOL (CIRCA 1830),

AMERICAN SCHOOL (CIRCA 1830), PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG MAN WITH BOOK Oil on panel, unsigned, presented in a period hardwood frame with ebonized and gilt surface. -

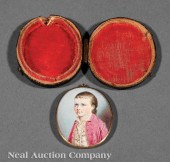

American School 19th c. "Portrait

American School 19th c. "Portrait of a Young Boy" miniature watercolor on ivory unsigned 1 3/8 in. x 1 1/8 in. in the original 18 kt. gold case with integral necklace loop and baize-lined skin case. Provenance: Descended in a Mobile Alabama family from New Orleans/Charleston.

American School 19th c. "Portrait

American School 19th c. "Portrait of a Young Boy" miniature watercolor on ivory unsigned 1 3/8 in. x 1 1/8 in. in the original 18 kt. gold case with integral necklace loop and baize-lined skin case. Provenance: Descended in a Mobile Alabama family from New Orleans/Charleston. -

American School (19th Century) A

American School (19th Century) A good unsigned miniature portrait of a gentleman with his elbow on a book and an American flag draped behind him framed under glass in a wide oak frame with gilt inner liner overall 7-5/8" x 6-3/4".

American School (19th Century) A

American School (19th Century) A good unsigned miniature portrait of a gentleman with his elbow on a book and an American flag draped behind him framed under glass in a wide oak frame with gilt inner liner overall 7-5/8" x 6-3/4". -

American oil on board portrait of a

American oil on board portrait of a young girl early 19th c. in a white dress with a blue ribbon 26 3/4" x 19 1/2". Provenance: New... ?

American oil on board portrait of a

American oil on board portrait of a young girl early 19th c. in a white dress with a blue ribbon 26 3/4" x 19 1/2". Provenance: New... ? -

AMERICAN SCHOOL, LATE 19TH CENTURY,

AMERICAN SCHOOL, LATE 19TH CENTURY, PORTRAIT OF YOUNG MAN WITH GO, UNFRAMED, 27 X 22 INAmerican School, Late 19th Century, Portrait of Young Man with Go, Unframed, 27 x 22 in

AMERICAN SCHOOL, LATE 19TH CENTURY,

AMERICAN SCHOOL, LATE 19TH CENTURY, PORTRAIT OF YOUNG MAN WITH GO, UNFRAMED, 27 X 22 INAmerican School, Late 19th Century, Portrait of Young Man with Go, Unframed, 27 x 22 in -

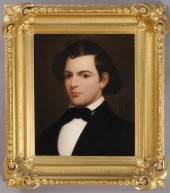

AMERICAN SCHOOL, PORTRAIT OF A

AMERICAN SCHOOL, PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG GENTLEMANAmerican School19th centuryPortrait of a young gentlemanoil on canvas30 x 25in (76 x 63.5cm) Provenance:Property from the Estate of Gregory Warren Nelson, Reno, Nevada.

AMERICAN SCHOOL, PORTRAIT OF A

AMERICAN SCHOOL, PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG GENTLEMANAmerican School19th centuryPortrait of a young gentlemanoil on canvas30 x 25in (76 x 63.5cm) Provenance:Property from the Estate of Gregory Warren Nelson, Reno, Nevada.

...many more examples with full details are available to our members - Learn more